This historical introduction to the language of the law originated to answer the need for a classroom text for the SUNYBinghamton course in Legal Terminology. The course had its first run in the Fall semester of 1981, with the encouragement of Emilio Roma, director of the Law and Society Program, and Anthony Preus, chair of the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Studies. A Vice-President's Curriculum Development Grant fostered the early research. Dr. Martha Jean Schecter, Member of the Bar of Kentucky and of New York, combed the vocabulary to eliminate words and phrases that are no longer in current use, and made important corrections to many entries. Ms. Lovette George helped to winnow the list further. The contents have since been replanned and amplified. For their reading of the text and suggestions for its improvement I am grateful to Bert Hansen, Gerald Kadish, and Michael Mittelstadt, and the students of Classics 113 in 1981, 1982, 1983 and 1986.

CONTENTS

- Language and European History

- Legal History and Legal Terminology

- Litigation, Pleading and Trial

- History I: Roman Civil Law

- Contracts and Debts

- Judgement and Enforcement

- History II: Canon Law and Jus Commune

- Wills and Estates

- Penal Law

- History III: Germanic and French Custom, Feudal Law, Law French

- Domestic Relations

- Crime

- Documents, Instruments, and the Record

- History IV: English Common Law

- Real Property

- Criminal Procedure

- Equity

- Commercial Law

- History V: North American Reception of European Law

- Logical Argument and Evidence

- Torts

- Corporation, Partnership, and Securities

- Sovereignty and Conflict of Laws

INTRODUCTION

This book is about the technical language of Anglo-American law. It looks for the sources of that technical language in European legal systems of the past, and tries to see the language and the history each in the light of the other. Care has been taken to make the book readable and accurate, and every technical word, phrase and maxim has been listed in the index, in hopes of serving readers who will wish to use the book for their own pleasure and enlightenment as a discursive sketch of legal antiquities or as a reference tool.

The selection of legal terminology presented here is far too meager to lay claim to being a legal dictionary. There are fewer than 900 items, counting words, phrases and maxims. I have tried to limit the word list to language that 1) occurs in current usage and that 2) has links, especially French and Latin links, to medieval and ancient law. For current legal usage, Black's Law Dictionary is recommended. The etymology of borrowed and naturalized English terms should be pursued in the Oxford English Dictionary, and classical Latin background in the Oxford Latin Dictionary. Similarly, the sketches of earlier legal systems which are presented here do not amount to a history of law; for that reason, each historical chapter is accompanied by a short supplementary bibliography.

Finally, this book makes no contribution to the sociolinguistic, philosophical and ethical questions raised by the jargon called Legalese, or the impact of obsolete language on legislation and legal communication, or the debate over clarity and precision. For these matters, the definitive survey is David Mellinkoff, The Language of the Law. Further explorations in social linguistics are found in Shirley Brice Heath, "The Context of Professional Languages: an Historical Overview" in Language in Public Life (1979), pp. 102-118; and William M. O'Barr, "The Language of the Law" in Language in the USA (1981) pp. 386-406. The eloquent and useful guide by Henry Weihofen, Legal Writing Style (1961) gives solid practical advice and good remedies for pathological Legalese.

Back to the Table of Contents

1: LANGUAGE AND EUROPEAN HISTORY

At the beginning it should be useful to define the subject of the book and to identify its place within the large complex of the sciences of language. This book is about etymology, the history of the meanings of words. Linguistics and grammar have something to contribute to this investigation, but they are not essential to it. Not the whole English vocabulary but only one technical subvocabulary, legal terminology, is under consideration here. The method of investigation is historical rather than analytical.

Ordinary spoken English has borrowed thousands of words and wordelements from Latin and French. The technical vocabularies of scientific English are full of terminology adopted from Greek and Latin. It is possible, therefore, to analyze the foreign components of general English, or the technical language of the physical sciences, and use that analysis for further understanding and vocabularybuilding. For example, the Latin prefix sub appears in hundreds of words, such as suffer, subordinate, and support, always with a meaning related to its Latin meaning, "under". There are four Greek wordelements in the word electroencephalogram which add up to its meaning, "an electronic map of the brain". These are demonstrations of analytical etymology.

The language of Anglo-American law confronts the student with a very different sort of problem. The law is a partially selfcontained culture within the general one. Most of the time, lawyers speak ordinary English, but 1) they have special meanings for many words, and 2) they have a special, professional memory of other words and phrases from Latin, French, and oldfashioned English, that come from earlier stages of the study and practice of the law. A general analysis does not get us far toward understanding this professional dialect; it only shows us that most of the foreign elements were originally Latin and that most of these passed through French into the lawyers' English. Beyond that, each word or phrase must be examined for its own individual history within the tradition of the law. Some grand movements in the history of language must be understood, however, because they set the general context for our study of specifically legal English.

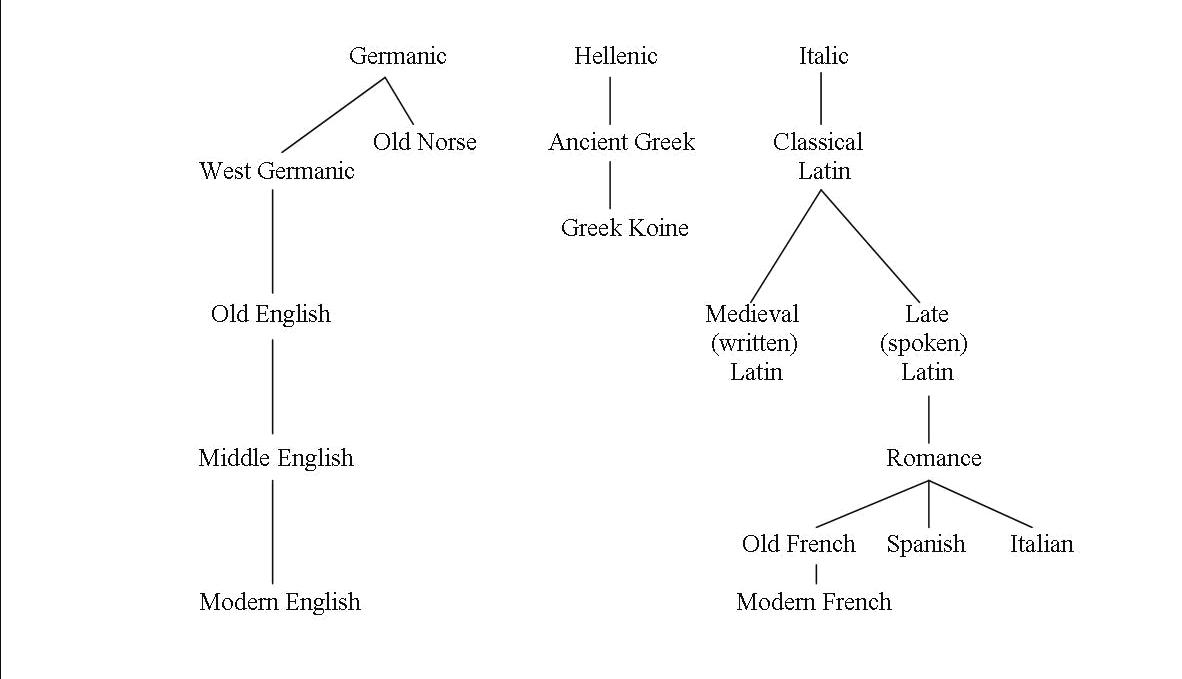

SOME INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES

The table above shows the family relations of the various languages that appear in the study of English legal terminology. Each arrow in this (very selective) table indicates the passage of time and the changing of a language, under constant use by large numbers of speakers and writers, into a noticeably different language. Latin, the language of the ancient city of Rome and its empire, became the language of all of Italy and of Gaul (modern France) as the empire expanded. When the empire collapsed, beginning in the 4th century AD, the intercommunication between its regions, which had kept their language more or less unified, became rare. Late Latin or Primitive Romance was spoken more and more differently in the different countries of Western Europe. In the course of fifteen hundred years, Romance divided into different modern languages including the two that we know as Italian and French. Both are descended from Latin, and their vocabularies are mostly derived directly from Latin. For example, the Italian giudice and the French juge are both derived from the Latin judex and mean the same thing: judge.

English, as the table clearly shows, belongs to an entirely different branch, the Germanic branch, of the Indo-European language family. English is not descended from Greek or Latin, much less from French. Why, then, does it contain so much vocabulary material from those languages? And in particular, why does its specialized legal terminology come mostly from Latin and French?

English culture and the English language have inhabited the same home island of Great Britain since the Anglo-Saxons invaded it from the continent in the 4th century AD. There has been only one military conquest of the island since then the invasion of the Normans under William the Conqueror in 1066, which gave England a Frenchspeaking ruling class. The Normans then monopolized warfare, the land, the land law and the courts, in French, for three centuries.

In a sense, England succumbed to two more purely linguistic invasions. Through the whole Middle Ages in Europe and England, roughly from 500 to 1500 AD, the Christian Church and its clergy held a near monopoly of literacy and booklearning, including legal records and legal scholarship, all in Latin. And Greek made its mark on all the European cultures because it was the original language of the New Testament, as well as of western mathematics, logic and technical grammar, philosophy, medicine, and the natural sciences.

So it happens that the English language, due to the domination of England by a Norman military aristocracy, and centuries of respect for religious authority and professional expertise, now has a vocabulary which is mostly borrowed from French, Latin, and Greek. England's Law Latin is a fragment of Medieval Latin; and Law French is Old French as it was spoken in the law courts of England.

Respect for authority is a strong element in Anglo-American culture. At its best, this respect is what causes us to give generous recognition and rewards for excellent achievement in the arts and sciences, regardless of the family background and personal style of the achiever. At its worst, it is silly snobbery. In between, in daily life we tend to assume that what we are told by the doctor, the minister of religion, and the legal specialist is true and worthy of respect. If their language is somewhat difficult to understand, we normally do not resent this; in fact we expect high sophistication to sound sophisticated. When we acquire a little or a lot of professional knowledge, we use the professional terminology to express it. On their side, the learned professionals are accustomed to learning their craft, then discussing and practising it, in a language that they share fully only with their fellow professionals. They do not object to sounding like doctors, priests, lawyers; instead, they enjoy the spontaneous respect it brings them from the rest of society. Furthermore, they use their technical language as a professional dialect "jargon" is the pejorative term that unifies the members of the professional group and excludes outsiders.

It would be useful at this point to distinguish three levels of reception of foreign words into a language (English in the present case): borrowing, adoption, and derivation.

- Borrowed words are picked up from other languages by some English speakers for the sake of their usefulness, but they are not changed in their forms (except by mistake), and they do not become truly English words, that is, part of the general vocabulary of the language. The Latin mens rea and the French feme covert are examples of borrowings.

- Adopted words have become English words, but with little or no change in form, like the formerly Latin per diem or alibi, or the formerly French demurrer.

- English derivatives may have come into the language by adoption, but over time they have changed form to look and sound more English, for example jail (older English spelling gaol) came from the Latin caveola, "little hole"; judge and jury are from the French juge and juree.

Terminology

There are nearly one thousand terms and maxims under consideration in this book, distributed among the following chapters. Chapters 1 and 2 are about language and legal history in general. Chapters 4, 7, 10, 14 and 19 deal with the history of law, concentrating on the legal systems of the past that have provided terms for our legal language. The other chapters explain a sampling of the terminology of particular legal topics such as Real Property and Torts. It will be obvious that many of the terms could just as well have appeared under different headings, and I do not mean to imply that sua sponte, for instance, is exclusively associated with procedure because it appears in the Pleading and Trial word list.

The word lists in this textbook are not intended to substitute for a dictionary. While I have attempted to include only words that are in current use, the explanations that are given here concentrate on origins and traditions rather than modern usage. For an uptodate technical understanding of any word, a legal dictionary such as Black's or Ballentine's must be consulted, and for more linguistic and etymological information, the Oxford English Dictionary.

These symbols are used in brackets to explain the linguistic history of a word:

- > translated to

- A Arabic

- E English

- F French

- G Germanic in general

- H Hellenic, i.e. Greek

- I Italian

- L Latin

- N Old Norse

For example, the entry habendum [GE>L] indicates a Latin word which entered the legal vocabulary as a translation of the Germanic and English phrase to have [and to hold]; cede [LFE] was once the Latin cedere and later the French ceder.

Quotation marks indicate a translation or other rerendering of the word or phrase, a replacement definition. The following abbreviated Latin notes are used with their customary meanings:

cf. = confer, compare e.g. = exempli gratia, for example i.e. = id est, that is q.v. = quod vide, and see that

A suggestion is in order about the pronunciation of the foreign-language terms. French has its own proper standards of pronunciation, and Latin has more than one: a classical pronunciation and a medieval (alias the ecclesiastical or Italianate) pronunciation. In a way, it might be more correct to pronounce legal Latin according to those rules, and some lawyers do so. But it is more common and therefore correct to speak technical legal French and Latin words, especially the latter, as if they were English, e.g. "fiery fayshes" for fieri facias. Current pronunciation by lawyers should be followed, and Black's Law Dictionary shows what that is. When in doubt, speak boldly.

Until this century, lawyers were expected to have been educated in the Liberal Arts including Latin grammar, and the Latin fragments which survive in technical legal language are grammatically correct Latin. A user who does not understand Latin grammar should refrain from tampering with them unassisted, since a single letter changed can alter the grammar and change or empty the meaning of the word. Even commonplace rules can fail: the familiar plural of datum is data, and so forum has the plural fora; on the model alumnus alumni, several guilty men are rei. But corpus is a neuter from a different group, and its plural is corpora; onus has the plural onera. The noun actus is masculine, but its plural is also actus; similarly, prospectus prospectus. But there is also an adjective actus, which appears in the phrase res inter alios acta, whose plural would be res ... actae. The correct plurals actus rei, mentes reae, corpora delicti or (when several crimes are meant) corpora delictorum do not come naturally to a non-Latinist. The reflexive se and its adjective forms including sua signify masculine, feminine, and plural persons without change of form. In the word lists of this book, Latin plurals are given where they might be useful. Caveant emptores.

Back to the Table of Contents

2: LEGAL HISTORY AND LEGAL TERMINOLOGY

When our contemporary lawyers talk about law, a large part of their peculiarly legal vocabulary consists of Old French, antique English, and Latin words and phrases. These are a part of their professional heritage from a tradition of the science and practice of law that goes back to the Roman republic, four centuries BC, and that has other roots in the medieval Germanic nations of Europe.

Our Legal Tradition in Brief

One good way to begin a systematic study of legal words and phrases is with a general understanding of the legal systems of the past in which they were generated. The purpose of this book is to explain the terminology historically, and vice versa, to illustrate the legal history with the terminology. The chapters that follow are a mixture of historical sketches and topical surveys of the language. Here is a short summary history of the legal traditions, keyed to the diagram.

Ancient Roman Civil Law became known throughout Europe in the form of the Emperor Justinian's 6th-century Corpus Juris Civilis, but not until five centuries after the Corpus was compiled. This massive, complete written legal system was recovered late in the 11th century and put to use as 1) the law of the German Holy Roman Empire, which considered itself the successor of the ancient Roman Empire; 2) the law used and enforced by cities and states in much of the old Roman-Law territories, especially in Italy and southern France; and 3) the graduate course in legal theory taught in the medieval universities, including the English ones, which came into being in the 12th century.

The law of the western Christian Church, which developed in Latin, within the Roman Empire and under the influence of Roman Law, was codified beginning in the middle of the 12th century. This "Canon Law" applied to church people and church cases in England as everywhere else in western Europe. For convenient handling of interstate cases and mercantile law, Civil and Canon Law were blended into a judges' common law, the Romano-Canonical jus commune.

The Germanic tribes and nations had their several customary laws, unwritten but memorized and woven into the German languages, including Anglo-Saxon. One federation of German tribes, called the Franks (or "Free Men") after they had invaded Roman Gaul in the 3rd century, adopted the local Romance language but maintained their German customary laws. The land and language then took the names France and French, after the Frankish invaders. In the 9th century the Scandinavian Northmen or Normans, also Germanic peoples, invaded the northwest corner of France, which is still called Normandy after them, and repeated the same translation process. When the ormans invaded England in 1066, they brought their customary law with them (in French), and this continued as the law of their class privilege, feudal law.

Beginning in the 12th century the Norman kings of England worked to centralize the laws of the island under their control, but without homogenizing them. England kept a national law of many systems and three languages: the Old English of the majority of the population, the Norman French of the dominant class, and the Latin of the literate clergy. The kings' justice, applied in common throughout the realm, was the English Common Law. At its beginning, this system dealt with only a few questions of private land law and a few criminal matters.

Amplified by Statutes and supplemented by courts of equity such as Chancery and Admiralty, the Common Law developed into a true national law, although it was not represented in University studies until 1758, when William Blackstone took the Vinerian Chair at Oxford and began the lectures which he published in 1765-1770 as his Commentaries on the Laws of England. This first general textbook included and explained the law's linguistic oddities. English-speaking Canada was a legal outpost of Great Britain, subject to the legislation of Parliament at Westminster and observing the precedents of the British courts. The United States too, although they were free after the Revolution to choose their own laws from any of a half-dozen sources, gravitated toward the law as found in a few English books, especially Blackstone, and so the British legal tradition, as represented by Blackstone, became the major original source of North American law and of almost all its foreign-language terminology.

Back to the Table of Contents

3: LITIGATION, PLEADING AND TRIAL

The law is strongly conservative in some ways, and the ritual of the courtroom is a notable example. The trial space and its traditional arrangement and furniture contribute to the sense of a special, even a sacred or magic event. The judge's bench, elevated on its tribunal over the verbal fight that takes place in the well of the court; the jury in its box, enclosed and safe from tampering; the public seats outside the bar these are all liturgical traditions we have inherited from what might be called English architectural procedure. We would still have the prisoner standing in the dock, if we were not so sensitive about dramatizing the presumption of innocence. The orderly sequence of trial is part of "due process", but it is also part of the ritual, traditional character of justice at work. In fact, according to an older idea, "due process" was "due" or "owed" not so much to the weaker party as to the dignity of the law and the court. Even in a democracy, we like our formal justice to look regal and divinely detached. In the dictum of Lord Hewart in R. v. Sussex Justices (King's Bench Reports 1924, vol. 1, p. 259), "Justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done"; and we want it to look like justice, solidly traditional, even antique.

We want it to sound like justice too, with formal English prose in the pleadings and with atavistic cries and traditional formulaic proclamations like "Oyez! Oyez!" and "God save the United States of America and this honorable court!" The terminology associated with judicial procedure is highly traditional, harking back to the English courts of the long age when their spoken language was French and their record was usually kept in Latin. In the word list for this chapter, about a third of the entries have a French history, and the only Anglo-Saxon ones, answer and hearing, were introduced to translate the Latin terms responsio and auditio because the latter sounded too Civil-Law for the English lawyers' taste.

A great American historian of legal procedure, Robert Wyness Millar, traced 23 terms in his article "The Lineage of Some Procedural Words", American Bar Association Journal 25 (1939) 1023-1029. Ten items in the following list, and more later, are marked with citations to Millar. References to Broom in this and later chapters refer to Herbert Broom, A Selection of Legal Maxims, Classified and Illustrated (7th American, from the 5th London edition; Philadelphia, 1874).

TERMINOLOGY

action [LFE] a lawsuit; this is the meaning of the Roman Civil

Law term actio, brought by the actor or plaintiff (Millar, p. 1024).

actionable [LFE] capable of being a cause of a lawsuit.

ad damnum [L] "to the loss", the first words of the

paragraph in a complaint that states the value of the loss.

ad hoc [L] "for this", for one purpose only, as an attorney

ad hoc represents a client only for one action or even for only one hearing. The plural would

be ad haec.

ad litem [L] "for a lawsuit"; a guardian ad litem is not

a guardian in general, but only a law guardian.

ad testificandum [L] "for testifying"; one purpose of

a writ of habeas corpus; one kind of subpoena (cf. duces tecum below).

adjourn [LFE] "[put off] to a day"; to postpone a trial,

sometimes (illogically) sine die, "without a day" to reconvene.

affirmative defense [LE] one that establishes

(Latin ad + firmat) a fact; by contrast, a negative defense disproves

the complaint or charge.

allegation [LFE] From the Latin ad + legatio,

"a message": the setting out of facts or claims that one intends to prove.

amicus curiae [L] "friend of the court",

characterizing a person, not a party to a lawsuit, who files a brief in the public

interest or to help the court serve justice. The feminine amica curiae might be used,

or the plural amici curiae, but not if the phrase is to function as an adjective.

Audi alteram partem. "Hear the other side." A

Latin maxim explained by Broom (pp. 112-116) principally in criminal procedure: "No

man should be condemned unheard". The law must inflict no penalty on one who has not

been allowed to answer. Broom quotes Justice Fortescue: "The laws of God and man both

give the party an opportunity to make his defense, if he has any." It may be that

Fortescue was thinking of the argument, at least as old as Bartolo, that even the Creator

gave the first man his day in court with the summons "Where art thou, Adam?" (Gn.3.9).

answer [L>E] a "swearing back", from the Old English andswaru,

to translate the Latin responsio (Millar, p. 1026).

bar [LFE] From a presumed Late Latin barra, a pole used as

an an obstruction; an impediment to a contract or to a lawsuit; or the physical boundary

that separates the owners'portion of a court, a legislative chamber, or a tavern from

the public part.

brief [LFE] "something short": the summary of a case made before

or after trial; in England, the summary prepared by the solicitor for a trial attorney, on

which is marked the fee that will be paid for pleading it in court. The Latin breve

was also the term for one of the original writs of Common Law.

cede [LFE] "yield (Latin cedere)": to surrender or hand over

to another. The form concede is used in reference to a point at issue in an argument.

claim [LFE] "cry (Latin clamare)", "complain": to demand a right.

complaint [G>FE] "a cry": the French translation of Klage,

which is still the German word for an action at law (Millar, p. 1026).

contingent fee [LE,GFE] From the Latin con +

tangens, "leaning", "depending"; a fee that depends upon the attorney's success,

a fee "on speculation" or "on spec".

coram [L] "before the face of" a judge; so a writ of

error coram nobis, "before Ourselves", brought the case to the Court of King's Bench.

counterclaim [LFE] a claim by the defendant back against

(Latin contra) the plaintiff; its amount is called the setoff.

court [LFE] not from from Latin curia, which it often

translates, but from cohors: a barnyard, gathering of animals or soldiers, a city

ward, its assembly, and finally the formal gathering around the king or before

a judge (Millar, p. 1024).

de bene esse, d.b.e. [L] "out of wellbeing", "for

the good it might do": provisional and provisionally permissable, as is a deposition

taken before trial, if the witness is dying.

defendant [LFE] the one repelling (Latin defendens) an attack.

De minimis non curat lex. A Latin

maxim well translated by Broom (pp. 142-145) "The law does not concern itself with trifles."

For example, there are levels of damages below which courts refuse to hear in first instance

or on appeal, and minor casual nuisances, e.g. in water and land use, are simply ignored by the law.

demur [LFE] "dwell (Latin de + morare)", "abide",

"take a stand"; therefore the noun demurrer, originally the infinitive of the French verb,

means the defense's stand that the plaintiff's allegations do not oblige the defendant

to answer (Millar, p. 1027). Cf. demurrage in chapter 18.

de novo [L] "newly", "again from the beginning".

deposition [LE] "a setting down (Latin de + positio)"

in writing of testimony for the court.

dilatory [LE] From the Latin latus, "broad"; "tending to delay"

the course of a trial.

duces tecum [L] "you should bring with you" specific

documents or material evidence: one kind of subpoena.

esquire [LFE] "shieldbearer", a noble not yet a knight; so an

honorific for any gentleman in England, Canada, and other Commonwealth countries, and for an

attorney in the United States.

exception [LE] in Civil procedure, an exceptio was an

unfulfilled condition necessary to an action, or the defense's allegation that such a condition

was unfulfilled; later, any objection intended to bar or delay, by either side against

the other; cf. objection below (Millar, p. 1027).

ex parte [L] "from a side": refers to a proceeding that

involves only one of the parties to a lawsuit.

forum non conveniens [L] "inappropriate

court", a reason for which a court may decline to hear a case.

gravamen [L] "heaviness", "burden": the material heart

of a complaint.

hearing [L>GE] translates the Latin auditio.

in camera [L] often translated "in chambers": before a

judge, but in his private room (camera usually meant a bedchamber), not in public.

in invitum [L] "[proceedings] upon an unwilling person".

The feminine would be in invitam, plurals in invitos or in invitas.

interlocutory [LE] "in the midst of the talking

(Latin inter + locutus)": before the end of a suit.

interrogatory [LE] "questioning between (Latin inter +

rogatus)" parties, for the sake of discovery.

joinder [LFE] From the Latin jungere, the French

joindre, "a coupling together", e.g. the combination of several interests in one lawsuit.

letters rogatory [LFE,LE] a letter from a court

"questioning", i.e. containing interrogatories to be answered under the order of another court.

mesne [LFE] "middle", neither first (original) nor last (executory) process.

motion [LE] act of a party to move (Latin movere) a suit along

toward a conclusion.

ne exeat [L] "lest he depart", a writ forbidding a person

to leave the jurisdiction of the court.

nolle prosequi, nol. pros. [L] the declaration

by a plaintiff or prosecutor "that he does not wish to pursue" a claim or charge.

nonsuit [LFE] failure of the plaintiff to proceed or to prove

a case; a dismissal for that reason; a judge may be said "to nonsuit" a plaintiff.

objection [LE] "the throwing in (Latin ob + jacere)"

of an exception; the modern word for what the Civil Law called an exception.

of course [L>E] translates de cursu, "from the ordinary

sequence of events"; for example, a writ of course is issued on request, without need for

any argument of the merits.

pendente lite [L] "while a lawsuit is

pending (hanging)" as in the maxim Pendente lite nihil innovetur. "While a lawsuit

is pending (hanging), nothing new

should be done.". Lite pendente is also found, and the noun phrase lis pendens.

petition [LE] "a seeking", in Civil Law the quest for a right

such as an inheritance; any prayer for justice addressed to a judicial authority (Millar, p. 1026).

plaintiff [LFE] From the Latin planctivus, the French

plaintif, "the complaining one".

pleading [LFE] From the Latin planctus, a persuasive speech;

the oral arguments in a case, which is what the French plaidoyer still means (Millar, p. 1025).

pro bono publico [L] "for the public good", legal

services provided free of charge; sometimes reduced to pro bono.

process [LE] "a stepping forward". Processus was the late medieval

term for a particular lawsuit, while ordo judiciorum meant what we call "procedure", the

proper manner of conducting various processus. See Millar, p. 1023.

pro se [L] "for himself/herself/themselves": not through

an attorney or by proxy.

respondent [LE] "answerer" to a bill in equity or to an appeal.

retraxit [L] "he [the plaintiff] withdrew" his claim:

a bar to further action.

scire facias [L] "you should let [a party] know", an

obsolete writ for processes based on the record.

show cause [L>E] the court's order for a party to appear

and give reasons why the court should not take particular actions. Translates the

Latin ostensurus quare.

sua sponte [L] "by his/her/their own wish", voluntarily.

suit, sue [LFE] From the Latin sectum, "a following", "a pursuit"

(Millar, p. 1024).

toll [LFE] "to lift (Latin tollere)": to suspend the running of a

specified term, e.g. under a statute of limitations.

traverse [LE] "a crosswise position (Latin trans + versum)",

formally denying a plea in common law.

vacate [LE] From the Latin vacuum; "to empty", annul, cancel,

e.g. a judgement.

witness [E] In Old English, originally, "knowledge", later

"testimony", and eventually "the one who gives testimony".

A brisk survey is provided by John Henry Merryman, The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction

to the Legal Systems of Western Europe and Latin America (Stanford, 1969).

Paul Vinogradoff, Roman Law in Medieval Europe (2d ed. Oxford, 1929, repr. London, 1968)

is a classic account by regions; for England, see pp. 97-119.

The rather surprising Scots Law story is in Thomas B. Smith, Scotland: the Development of its

Laws and Constitution (London, 1962), especially pp. 124 of the "Historical Background".

censor [L] an officer of the Roman republic who kept the

tax list or census and the list of the Senators. The censor could remove a name from a

list at his pleasure, especially for reasons of public turpitude. Hence our usage to censor

and censure.

client [LE] in ancient Roman society, a person socially and

politically dependent on a patron; the patron would appear for his clients in litigation.

code [LE] from codex, a book bound in the modern way rather

than a volumen or scroll. The title of official compilations of law by the emperors

Theodosius (438 AD) and Justinian (534 AD).

curia [L] from coviria, "assembly of men", the name of the

Senate hall in Rome, later applied to any sovereign assembly; not really the Latin original

of court, q.v. above in chapter 3) but often used as if it were.

edict [LE] "declaration", by a Roman praetor or elected judge, of

the new remedies he would provide in his court; later a permanent compilation of those

equitable reliefs.

federal [LE] relating to the union of Rome with its allies

in Italy by foedera or treaties.

forensic [LE] "of the forum", q.v.; "judicial".

forum [L] the central marketplace of Rome, site of its daily civic

business and its earliest lawcourts.

litigation [LE] from lis (plural lites), a formal

judicial process, brought by the actor and contested by the reus.

magistrate [LE] the Latin magistratus meant "the

superiority" [of the public over private interests], temporarily held by elected officials

in Rome. The word also meant an officer who wielded this superior authority. These

positions were primarily executive, only secondarily judicial.

plebiscite [LE] from plebis scitum, "opinion of the common

people", a popular referendum proposed by the tribune, which could make laws even against

the will of the Senate.

public [LE] from poplicus or publicus, "of the whole

people (populus)" of Rome, not of any one person, however powerful.

republic [LE] from res publica, "the public business".

reus [L] the one charged with a crime or private wrong,

"defendant"; also, "guilty", and so mens rea, q.v. in chapter 12.

riparian rights [LE] a category of Roman land law dealing

with properties along a river bank, ripa.

senate [LE] The Latin senex means "old man", and senatus

the public function of old men: the Roman council of state made up of the most senior citizens.

stipulation [LE] the old Roman form of oral contract, made

in public by the two parties, each of whom would accept verbatim the terms spoken by the other:

"Will you give this for such a price?" "I will give it. Do you promise to pay such a price?"

"I promise". Later the term for a specific point of agreement by the parties to a contract

or the attorneys in a lawsuit.

tribunal [LE] the bench or court of a Tribune (tribunus),

the protector of the rights of the common people in the city districts (tribus or tribes).

usufruct [LE] the Civil Law category for one level of right in

property, the "use of its fruits" without right to alienate it.

ab initio [L] "from the beginning"; a contract can be void

ab initio or can become void ex post facto

(see chapter 23 and the maxim

Quod ab initio ... in chapter 20).

accede [LE] from the Latin ad + cedere: "yield to", "consent".

acceptance [LE] from the Latin ad + cipere: "a taking",

and thereby implying agreement to the conditions attached to the giving.

accommodation [LE] an action "to the benefit (commodum)"

of another, not for a consideration.

accord [LE] a contract for solution of an injury, bringing "heart to

heart (ad cor)".

acquiescence [LE] "becoming quiet toward" a transaction, giving

t tacit and passive approval.

aleatory [LE] "with dice (alea)" or "gambling", said of a

contract in which performance is contingent on an uncertain event. A lottery ticket represents

an aleatory contract, and so does a casualty insurance policy.

Aliud est celare, aliud tacere. [L] "To

conceal is one thing, to be silent another." Broom (p. 781) explains succinctly that in a contract

of sale "either party may ... be innocently silent as to grounds [for finding fault] open to both

to exercise their judgement upon." If the bread for sale is visibly green, the baker is not bound to

warn that it is old.

amortization "bringing toward death (ad mortem)", the

gradual reduction of the agreed value of an asset over its useful life, until it finally has no

value at all.

arrears [LFE] debts "behind (arrière)" in payment.

assign [LE] as a verb, "point to (ad + signare)": to

transfer; as a noun, an assignee.

assumpsit [L] "he undertook", an early English writ to enforce

contracts that were not under seal, were oral, or were merely implied, like the one between a

barber and his customer. Indebitatus assumpsit was a writ of debt: "Being indebted,

he undertook".

attachment [GFE] From the Old French estachier, "a nailing

down", a seizure by court order. Stake is cognate to this word.

avoid [LFE] from the Latin ex + vacuum through the Old

French esvuidier "to make empty": to make a contract, a judgement, or some other legal

act null and void ("nothing and empty"). The word's similar sound and usage caused it to slip

into the meaning of evade in vernacular English.

badges of fraud [L>E] recognized suspicious signs, such

as fictitious consideration, or aliases for the parties, which justify a presumption of fraud.

This strange phrase was suggested by the maxim Dolum ex indiciis

perspicuis probari convenit:

"Fraud ought to be proven by clear badges".

bankrupt [GIFE] "broken bench", "broken bank", a term for "insolvent"

in the international Law Merchant. An early banker was a trader and contractor with a fixed stall

or bench in some trading exchange. If he defaulted, his place of business would be literally or

figuratively broken up (ruptum) by his colleagues.

bona fides; bona fide [L] "good faith";

"in good faith". The first is used as a noun, the other as an adjective or adverb.

breach of contract [GE;LE] note that this figure of

speech takes a contract to be a bond between the parties which one of them can break by

nonperformance.

chose in action (Alderman, pp. 1113-1114) [F] "a thing in

action", an intangible property, i.e. a right, which can be brought to court, while chose in

possession is a real thing in hand.

consensus ad idem [L] "consent to the same thing",

a meeting of minds in making a contract.

consideration [LE] originally a word for

stargazing (Latin sidera = "stars"), consideration can mean contemplation or the thing

contemplated. In English contract law from the 17th century, it is the prospective

gain that a contractor has an eye on, the quid pro quo (q.v.)

necessary for a contract and for its legal enforcement.

contract [LE] the "drawing together (cum + tractus)"

of parties to business, a legal bond between them, obliging both.

creditor [LE] "believer", a lender, who believes in the debtor,

trusting him to pay back a loan.

damages [LFE] the value or quantity of a loss, in Latin damnum.

And see compensatory damages in chapter 6.

debt, debtor [LFE] what is owed (debitum),

the one owing it.

default [LFE] failure (Latin de + fallere) to pay a due.

delivery [LFE] from the Latin de + liber; "freeing",

"release" of goods to their rightful owner; once also the release of a prisoner from jail.

discharge [LFE] "unload", to unburden from debt or bankruptcy.

The Latin carrus meant "cart"; the Late Latin carricare meant "to carry freight".

distrain [LFE] from the Latin dis + stringere, to take and

hold as a pledge for performance. The act is called a distress.

ex contractu [L] "from a contract", one source of causes of

actions; the other is ex delicto (see chapter 21).

Ex dolo malo non oritur actio. [L] "From a bad

fraud no action arises". A party who gained a contract by deception cannot enforce it

in court. See dolus malus in chapter 17.

Ex nudo pacto non oritur actio. "From a

bare agreement no action arises." Broom (p. 745): Where there is no

consideration (q.v. above) there is no real contract.

exoneration [LE] from the Latin ex + onera)

"unburdening" from an expense, duty, or the weight of an accusation.

Ex turpi causa non oritur actio. "From

a dirty cause no action arises". Broom (p. 731) summarizes that "an agreement to do

an unlawful act cannot be supported at law".

garnishment [GFE] "putting under guard (Middle French garnir)":

a judgement which attaches goods held by a third party to satisfy a debt.

gift [GE] a gratuitous assignment, without consideration.

hold harmless [L>E] under a contract, to promise

indemnity to the other party: "The seller holds the buyer harmless"; often used as an adjective

for a clause or agreement that does so: "the contract includes a hold-harmless clause". The phrase

translates the Latin tenere incolumem.

illusory promise [LE] one that plays a trick

(Latin lusus) by committing the promisor to nothing.

inchoate [LE] "just begun (inchoatum)", not fully formed,

unfinished. The contrary adjective might be executed (of a contract), registered

(of an instrument), or mature (of any right). Some ignorant persons have used "choate"

as if it were a word, meaning the opposite of this one.

indemnity [LE] from the Latin in + damnum:

"freedom from loss".

insolvent [LE] unable to break (Latin solvere) the bonds of debt.

joint and several [LFE] characterizes a liability for

debt as belonging to a whole group (Latin junctim, joined together) and to each member

of it (Latin separatim).

jurat [L] "he swears", used as a noun for the clause of an

instrument in which a notary or court officer certifies the authenticity of its signatures and seals.

liable [LFE] from the Latin ligabilis, "able to be bound",

owing a debt.

loan [NE] originally a gift or grant (Old Norse lan), later only a

temporary one.

mala fides; mala fide [L]

"bad faith"; "in bad faith".

meeting of minds [GE] a modern phrase describing one

condition for a valid contract: consensus ad idem (q.v.).

Modus et conventio vincunt legem.

"Custom and contract overcome law." Stated as a rule of law (no. 85) in the Liber Sextus

of Boniface VIII; Broom (pp. 690-698) exhausts the subject and quotes Erle, J. in summary: "Parties

to contracts are to be allowed to regulate their rights and liabilities themselves."

non est factum [L] "it was not done" the defense that

an instrument of contract was not actually made; especially if a party signed it mistaking it

for something else.

novation [LE] "making a new [contract]" by substitution of a new person

for one of the parties.

nudum pactum [L] "bare agreement", less than a contract,

lacking consideration, q.v. above. The plural would be

nuda pacta.

Cf. the maxim above, Ex nudo pacto...

nulla bona [L] a return by a sheriff to a writ of execution,

reporting that there are "no goods" to satisfy the judgement.

operative words [LE,GE] within a contract or other instrument,

the precise words by which the purpose of the document is accomplished. The Latin operare

means "to work".

pari passu [L] "on an even footing", said of creditors who

are equal, not ranked in priority for payment.

party [LFE] The Latin pars means "fraction", one side of a relation,

contract, political rivalry, or lawsuit.

peppercorn [HLE/GE] a grain of black pepper, representing minimal or

merely nominal definite value, as in "a contract with only a peppercorn of consideration".

4: HISTORY I: ROMAN CIVIL LAW

A. Civil Law History

B. Civil Influences on British Law

Suggested Reading

TERMINOLOGY

5: Contracts and Debts

TERMINOLOGY